|

| |

|

|

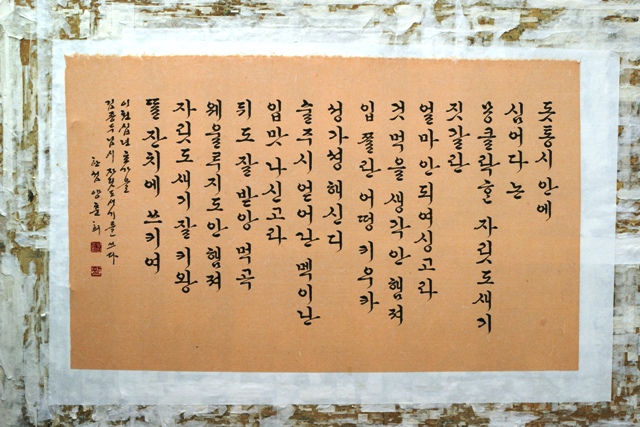

| ▲ Can the intricacies of the Korean language influence the way you think about life? Photo courtesy Jeju Province |

Learning a new language is far more than just cramming your brain with new vocabulary and learning a few grammar rules.

While this is certainly a big part of the process, learning a new language also has a subtle way of influencing the philosophy of your life.

As a humble learner of the Korean language, there are certainly some ways that it has influenced the way I think about my life.

| |

|

|

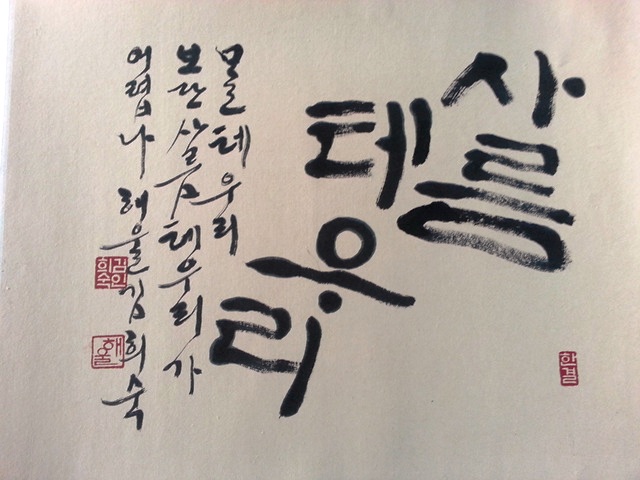

| ▲ Photo by Olivier Duong |

Focusing on the Uri (우리)

I am probably not making an outrageous statement by saying that the west is hyper-individualistic. In western culture, everything is about me, myself and I (It's even the name of a song!). Everything from magazines to music screams at you to put the self first.

That is in sharp contrast to the very modest use of the word uri (우리 we) in the Korean language.

I personally don't think that natives understand the paradigm shifting power of this word. If they have always used the word to designate themselves, they probably just associate it with ‘I’ without even thinking about it.

But for a foreigner, this word is powerful and challenges me every time I use it because it makes me think of all of it's implications. One can only be self-centered for long when the language forces a more communal view of things.

The phrases uri ane (우리 아내 our wife) and uri don (우리 돈 our money) sound weird when first used, but they help create an overarching sense of community, belonging and sharing.

It's no surprise then, that when Koreans open up a bag of snacks they pass it around until there are none left. It was uri in the first place, no?

| |

|

|

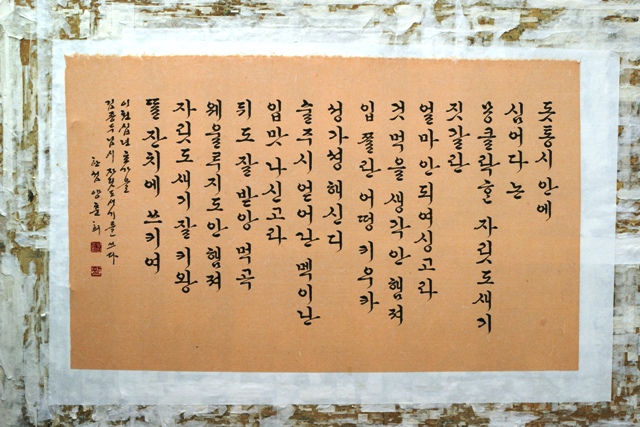

| ▲ Photo by Olivier Duong |

Age-based relationships

My mother was 10 years older than my father, but the way Korean is structured, I wonder how and even if they could have been together if they were living in Korea.

In language class, I was teasing my girlfriend, asking where her boyfriend was as I always saw her talking to this guy.

“Ani!” She said, “Namdongseng i ye yo!” (아니! 남동생 이에요 No, he is my younger brother!).

While I was just kidding I found her reaction interesting. It seemed that she didn't even contemplate the possibility of a romantic relationship since they were little brother and big sister.

I actually found myself branded as an oppa (오빠 big brother) before I knew what it meant. The peculiar thing is, just by hearing oppa enough times, I felt wise and felt that I had to live up to what I believe an older brother does best: help younger siblings.

Another time, I heard this kid call a friend's daughter nuna (누나 big sister) having never met her before. The general feeling I get in Korea is that everyone is part of a big family. This reinforces the sense of community that I don't find in western countries.

| |

|

|

| ▲ Photo courtesy Jeju Province |

The feeling and the self

Linked to western hyper-individualism is also the fact that the ego has been fused with the feelings we feel and the signals our body sends us. I AM hungry, I AM happy. It almost seems like the whole being is changed depending on how we feel. Essentially, we are what we feel.

But Koreans have a different way to express such things, be gopayo (배고파요 My BELLY is hungry), gibuni johayo (기분이 좋아요 My FEELING is happy). This seemingly innocent precision is important because it's a constant reminder that you are not your feelings and more importantly a reminder that you are free to choose your response to such feelings.

Philosopher Viktor E. Frankl said that “Man's last freedom is the ability to chose how he is going to react to any situation”.

This insight came to him when he was in a Nazi concentration camp and he realized that even after all his other freedoms had been taken away from him, he still had the freedom to choose how he reacted to the situation.

Such a powerful idea is much easier to put into action when your language is structured in such a way that it puts the emphasis on what is really being affected (like your belly) while presupposing an untouched ego behind it capable of choosing a reaction.

| |

|

|

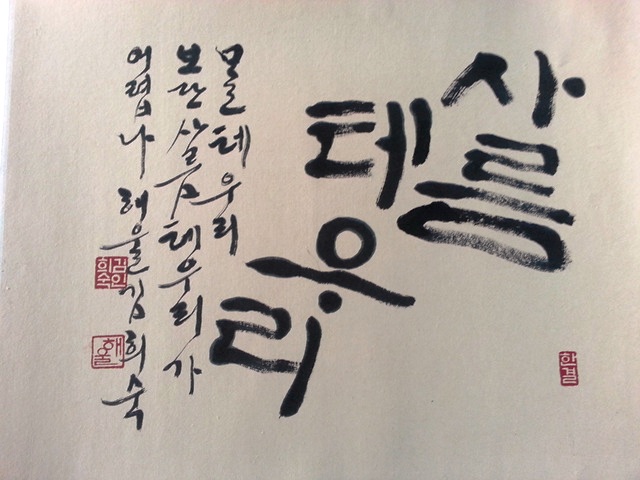

| ▲ Photo by Olivier Duong |

Embedded respect

Nim (님) is attached to functions and names to make them honorific. The thing that really stood out for me is that for many words where nim is attached, you cannot really remove it, the respect is built in and immutable.

As well as this, the Korean language has different levels to be used depending on who you are talking to.

Therefore, there needs to be a conscious effort to observe who you are talking to and your relationship to said person in order to use the correct form of language. This causes you to become conscious of your own status towards the people you are talking to.

The idea of respect is slowly but surely getting eroded in the western world. However, with the varying levels of politeness embedded in their language, I think it is safe to assume that Koreans won't have this problem.

The flipside of the equation is that respect can lead to an unwillingness to act from those who are of a lower social status.

Picture the situation; you are a nurse just out of college and you are about to perform surgery with a veteran Anesthesiologist who studied at Harvard.

Since day one you've used your lowest bow and you've spoken using the highest form of Korean. Now in the operating room, you blink twice as you cannot believe what the doctor is about to do. He is off by 500ml, this stuff can kill the patient! What would you do?

According to The Checklist Manifesto, you probably wouldn't stop it. This research found that because social proof is in full swing questions like “who am I to know what's right?” pop up in your mind.

Again, this is a universal problem, but one can see how when social status is embedded in the language, challenging authority could be even harder.

These are some of the ways learning Korean has influenced my philosophy. However there is still much to learn and it is a long road ahead. At the end of the day though I am a student not only of Korean, but also of life. |